“Groove and melody are 90% of a good song… but a good melody is a bastard to come by.”

-Doctor P

Legendary EDM producer Doctor P struggles to write melodies. So do you.

Fortunately, there are simple tricks to writing powerful and compelling melodies!

You’re about to find out that writing melodies can be incredibly easy. Don’t make it hard! I am going to teach you the three fundamental building blocks of melodies that every producer should know.

Are you a beginner with little musical knowledge? Fear not, this article is for you. I will help you write better melodies fast.

Get ready for inspiration to strike!

1. How to Learn Scales Fast by Using this Hidden Technique

I finally understand that musical scales are ladders.

No, literally, the word scale comes from the Latin word scala, which means ladder. And just like a ladder, scales have steps.

It’s important for you to use those steps because otherwise your melodies will slip, fall, and break their legs. Ever heard the sound someone makes when they break their leg? It’s not pretty, and neither will be your melody if you don’t use scales.

Let me tell you how to use musical scales effectively.

What are scales?

I can almost hear you thinking, “But what is a musical scale?!!” (If you already know, feel free to skip ahead.)

Let me lift the veil for you. Musical scales are simply a set of notes from which you can build melodies and harmonies. The most common scales only use seven out of the twelve musical notes in every octave. These notes can be played at any octave.

Scales make it easier to write melodies.

Why? Because (at least as a beginner) you should only use notes that are in the scale to write your melody. That means you have less notes to choose from!

Stay with me here, because this is important. Any scale can begin at any given note (called the tonic note, or key or root). Scales are defined by the intervals (space between notes) that they contain.

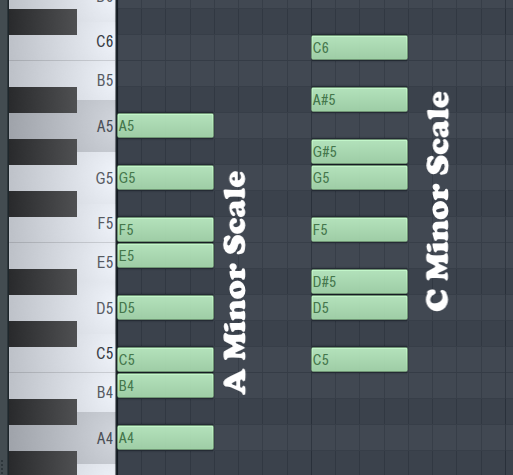

For example, the natural minor scale, which contains seven notes (or seven steps), consists of notes laid out in the following pattern: First note in the scale, +2 notes above the first note, +1 note above the 2nd note, +2 notes above the 3rd note, +2 notes, +1 note, +2 notes, and finally +2 notes. The minor scale starting on the note A and starting on the note C is pictured below.

And now you’re thinking, “how can there be two different minor scales?!!”

Let me break it down for you. Songs using the A minor scale (which is named as such because it starts on the note A) are said to be in the key of A minor. Similarly, songs using the C minor scale are said to be in the key of C minor.

Here’s the important part: Any note played that is in the scale is said to be in key, while any note not in the scale is said to be out of key (or chromatic). The same is true for the C minor scale.

For example, if a song were using the A minor scale, the note B would be in key while the note A# would be out of key. Similarly, if a song were in C minor, the note A# would be in key while the note B would be out of key.

4 Scales Every Producer Needs to Know

You have probably heard of the major and minor scales.

But here’s the big secret that so many producers use when they write melodies in major or minor: the major and minor pentatonic scales.

Let me tell you how to use these four scales to spice up your music.

1. The (Natural) Minor Scale

The natural minor scale is one of the most used scales in modern music.

You must be wondering when the minor scale is used. Well, it is especially popular in EDM, hip hop, and dance music. This is because the minor scale often is said to convey tension, energy, darkness, and sadness. All four of these emotions will add interest and drive to your song.

You guessed it. The minor scale contains seven notes, which are depicted below (in the key of A minor).

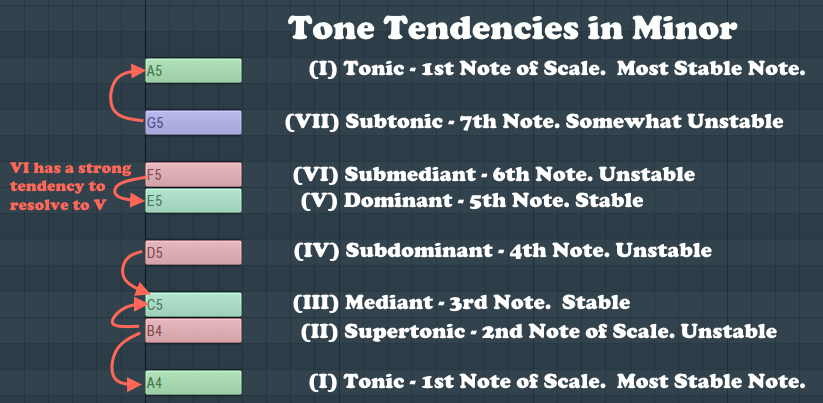

Important Side Note: Stable vs. Unstable Tones

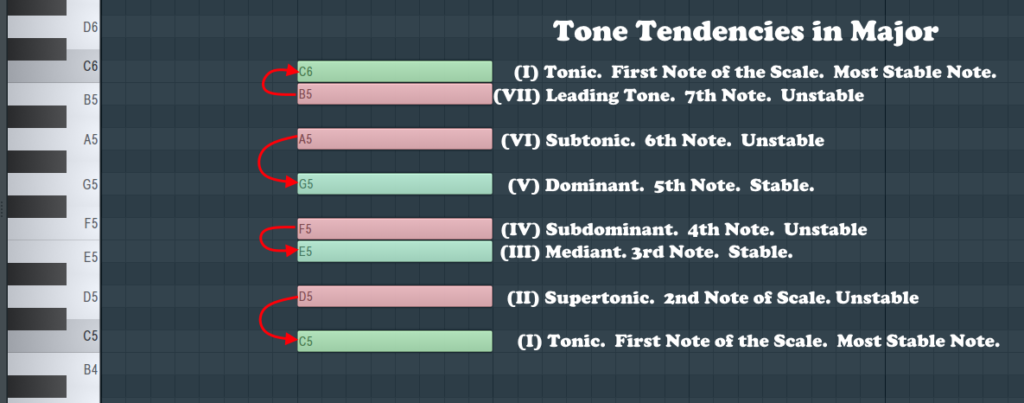

As shown in the above picture, some of the notes in the scale are considered stable, while others are not.

Why? All tonal systems are built in a hierarchical structure. There is always one tone (named the tonic) which is the most stable note in a scale. Other tones which have a good relationship to the tonic are labeled as stable.

The stable tones in the minor scale are I, III, and V.

Unstable tones are defined as having intrinsic melodic energy. They have a more distant relationship to the tonic note. When an unstable tone resolves to a stable tone, it creates a feeling of resolution and satisfaction. Unstable tones tend to resolve in a downward direction to stable tones.

This is why note II usually resolves to note I (but sometimes to III), IV resolves to III, and VI resolves to V.

Here’s the catch: VII, which often resolves to I, is a special case in the natural minor scale. It is more stable than the seventh note in most commonly used scales. Still, it is unstable enough that it tends to resolve upwards because the closest stable tone in the scale is above it.

Just like in a good story, it is important to develop a pattern of tension and resolution in music.

I’m sure you are with me on this: If there were no tension in a story, would it be interesting? Likewise, a melody would be boring without enough tension. If there were no resolution in a story, would it be satisfying or fun to read? Likewise, a melody with no resolution would leave listeners disappointed. Resolution adds a sense of forward motion to songs.

It all boils down to this: you must use both stable and unstable tones if you want compelling melodies.

Typically, melodies begin on the tonic note and quickly go to the dominant (or sometimes the subdominant) note. Even though the dominant note is technically stable, it is unstable enough that it typically wants to resolve to the tonic note, I. The tonic and dominant notes are typically the most important notes in a scale, and the tension between the tonic and dominant notes is the force that makes most melodies work in the major, minor, or pentatonic scales. The relationship between the tonic and dominant is extremely important.

Also, the subtonic and the supertonic, both being unstable notes, are the most common notes to end a melody upon in minor.

2. The Minor Pentatonic Scale

You guessed it: the minor pentatonic scale only has five notes, just as the name of this scale suggests.

I now realize that the minor (and major) pentatonic scale actually predates the minor scale. It existed and was used by musicians thousands of years before the minor scale was commonly used. While more “advanced” civilizations developed and used seven note scales, tribal peoples from around the globe continue to mostly use the five-note pentatonic scales to this day.

You won’t believe what researchers found: Almost every civilization on Earth developed the pentatonic scale independently of one another.

Amazing, isn’t it? This is a testament to the popularity of the pentatonic scale and how much it resonates with humans. It continues to be used in dance music, blues, pop music, rock music, and almost every genre on the planet. It is essential to know this scale.

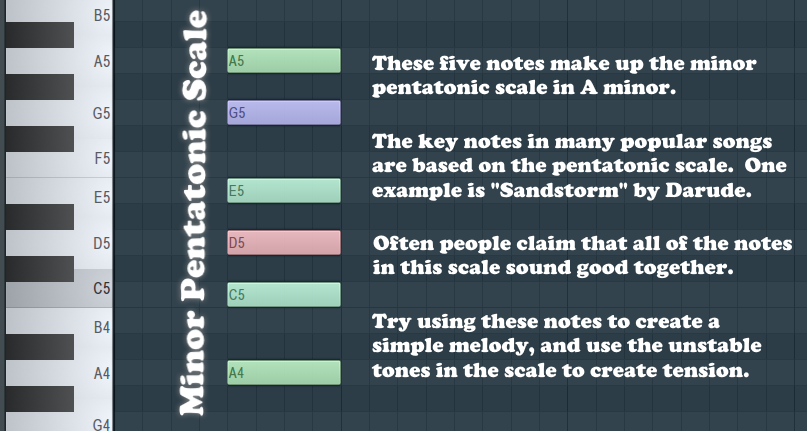

The best part is that the minor pentatonic scale consists entirely of notes that are contained within the minor scale.

Let me show you how to use this scale. In the image below, the minor pentatonic scale (in the key of A minor) is pictured. It consists of the first note of the scale, followed by +3 notes above the 1st note, +2 notes above the 2nd note, +2 notes, and +3 notes. The notes in this scale are often used as the pivotal (most important) notes in many popular melodies in the minor scale. A large portion of melodies in the minor scale consist entirely of the notes in the minor pentatonic.

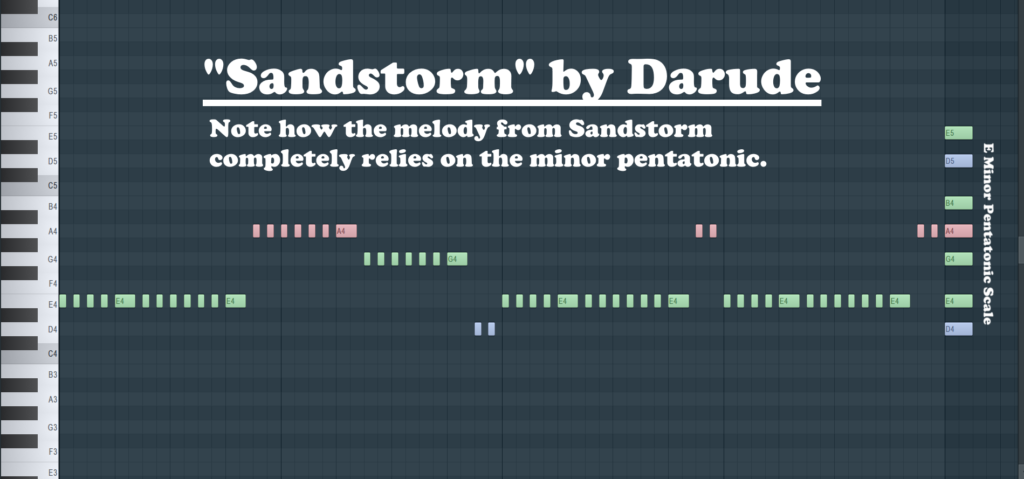

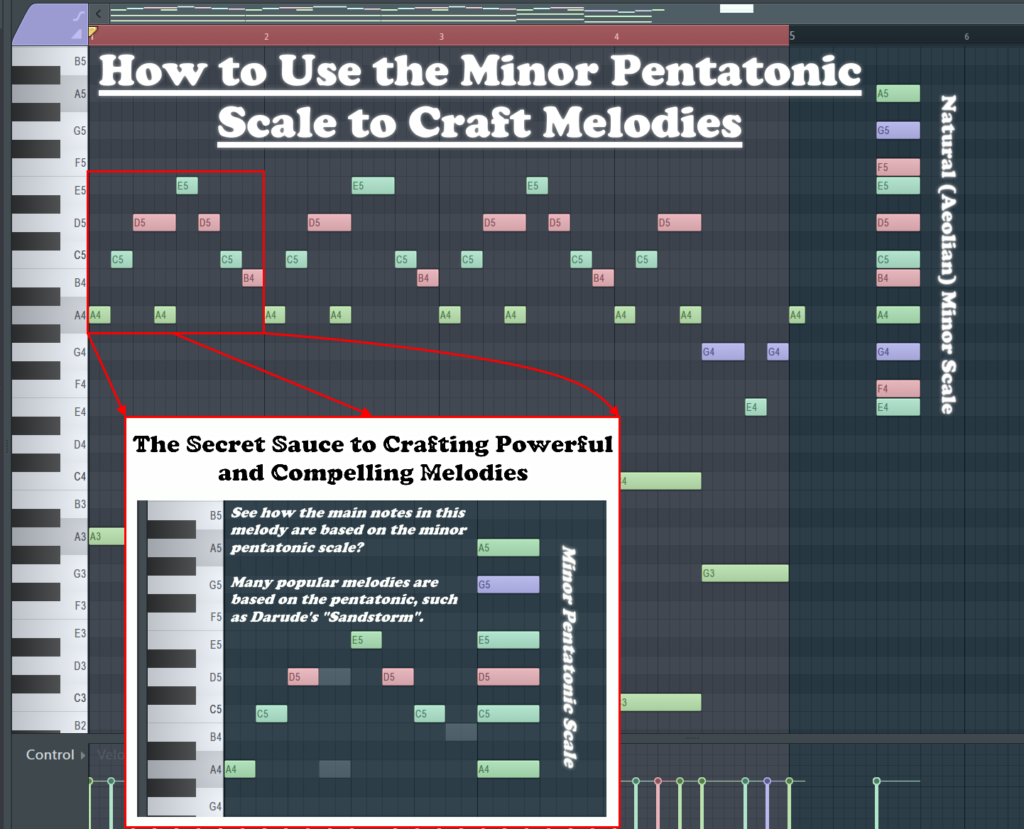

Below is the melody from the classic EDM song Sandstorm by Darude. Look at how the melody uses the minor pentatonic.

Often musicians will write a very simple melody using the minor pentatonic scale. Frequently these melodies will revolve around the notes I, IV, and V from the minor scale. The melody from Sandstorm above revolves around notes I and IV. Then, many artists will add additional, “ornamental” notes from the minor scale to add extra tension and interest to their melody.

Try writing the basic notes of a melody using only the minor pentatonic scale, then add in additional notes from the corresponding minor scale.

3. The Major Scale

Keep reading, because this is significant! The major scale is the most commonly used scale in music as a whole.

Here’s the interesting part: the major scale, which appears to predate the minor scale, has been used for thousands of years! Many musicians believe that the major scale sounds brighter and happier than the “darker” minor scale. Although the popularity of the major scale has been fading in the past decade, it remains one of the most used scales in modern music.

The major scale and its tone tendencies are pictured below (in the key of C major).

I’ll break this down for you. The good news is that the tone tendencies in major are extremely similar to those in minor. One key difference is that note VII is usually referred to as the leading tone rather than the subtonic. This is because the leading tone has an extremely strong tendency to resolve to the note one semitone above it (note I). Also, the supertonic only resolves downwards.

Let me tell you an important fact: the leading tone and the supertonic, both being unstable notes, are the most common notes to end a melody upon.

Here’s the bottom line. Once again, the tonic and dominant notes are the most important notes in the scale, followed by the subdominant. These notes form the basis of most melodies, which progress from the tonic (the most stable note) to the dominant (which conveys tension and a need to resolve back to the tonic), using the the subdominant to add interest and tension.

4. The Major Pentatonic Scale

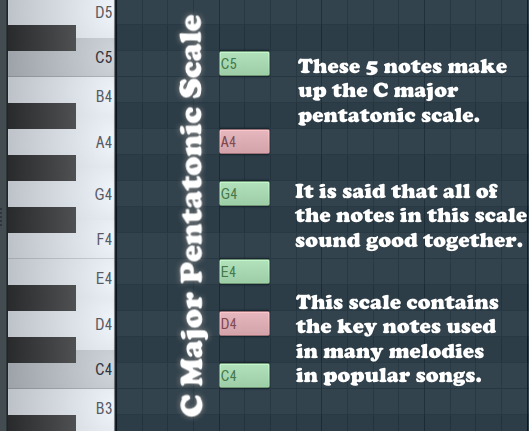

You won’t believe what I discovered! Just as the minor scale contains the minor pentatonic scale, the major scale has the major pentatonic.

And here’s the interesting part: the major pentatonic scale is the oldest known musical scale used by humans. All of the notes in the scale have a good harmonic relationship with each other, and therefore, they are said to all sound fairly good when played together/sequentially.

Since this is so important, let me show it you. The major pentatonic scale is pictured below.

Let me guess… is this scale is often used to write the pivotal notes in melodies that are written in the major scale? Yes! All of the notes in this scale also are contained in the major scale. The pentatonic scales are a useful songwriting tool because they narrow down the amount of notes that can be used in a melody and help make melodic structures sound better.

The Hidden Technique: This FL Studio Hack Will Make Writing Melodies So Much Easier!

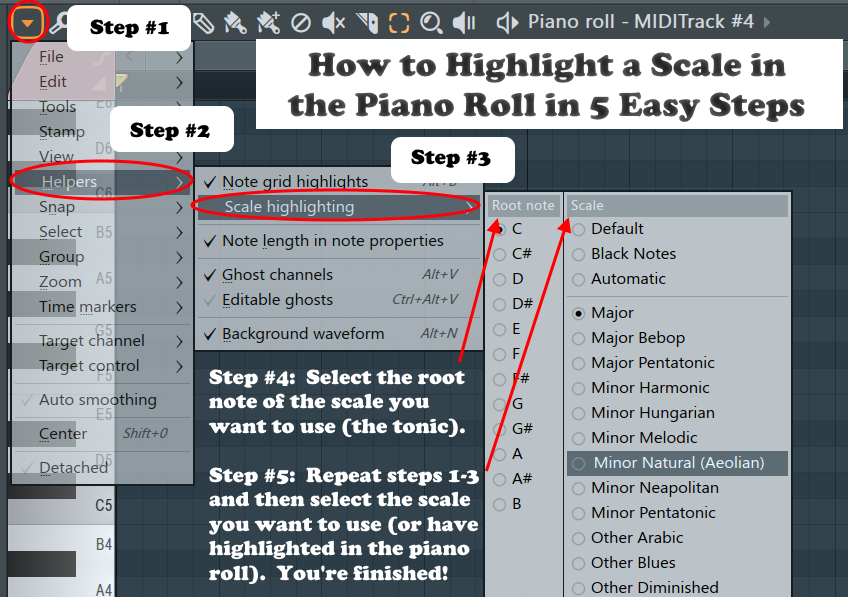

Don’t you wish that you could highlight a scale in the piano roll?

Guess what? You can! This makes it so much easier to write melodies.

Here’s how it works: When you highlight a scale, the piano roll will display all of the notes in the scale in a lighter color compared to notes that are not in the scale. This way, you can only use notes in the scale easily by only using the notes that are light colored.

How do you do this? The picture below illustrates the 5 easy steps you need to take to highlight a scale.

Select the major or major pentatonic scales to use those scales. As you may note, there are multiple minor scales listed. To use the most common minor scale (the one discussed earlier), select the “Minor Natural (Aeolian)” scale. Finally, you can also select and highlight the minor pentatonic scale.

This will make finding the correct notes so much easier when you write melodies!

2. What You Need to Know About Melodic Phrase and Motion

What exactly is a melodic phrase? A melodic phrase, much like a sentence, usually encompasses a complete musical statement.

But what does that mean? These melodic phrases typically define themselves by coming to some sort of resolution point (either rhythmically or tonally), much like sentences have periods. Phrases often resolve by either holding a note or resting (using empty space in the melody).

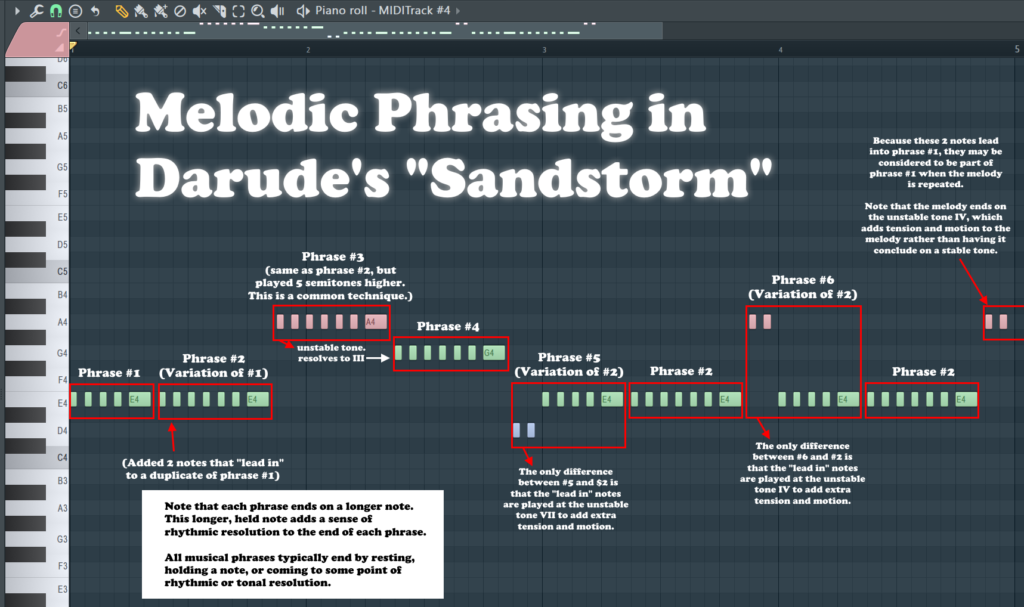

Below, the melodic phrases in Darude’s Sandstorm are highlighted and discussed. Click on the image to enlarge it.

Phrases can be grouped together to form longer phrases, or sections, of music.

Melodic Motion

Now, this is important. There are 2 types of melodic motion: conjunct motion and disjunct motion.

But what exactly is the difference between these two types of motion? Conjunct motion involves moving step by step from one scale degree to the next (for example, from note I to note II to note III). Disjunct motion involves moving by multiple scale degrees, for example, from note I to note IV. Disjunct motion most commonly involves jumping by either 5, 7, or 12 semitones. Note that in Darude’s Sandstorm, the melody jumps from the tonic (I) to the subdominant (IV) in the beginning of the melody. This is a common example of disjunct motion.

Most vocal melodies are comprised of conjunct motion (as that is easier to sing), but disjunct motion is also often used to add melodic interest.

3. How to Use Rhythmic Stresses the Right Way

Here’s something we can both agree on. Using rhythmic stresses tactfully is extremely important when writing a melody.

What is Rhythm?

Music, like all things in life, takes place in time. It is through the control of time that a musician proves their mettle.

Here are terms you need to know to understand rhythm! Pulse is defined as a series of undifferentiated even beats. Meter is the grouping of pulses, or a measurement of the number of pulses between regularly occurring accents. Music that stresses body movements, such as dance music or marching music, generally has a strongly implied or stated meter.

Don’t stop reading now, because rhythm, which can be measured by its relationship to meter, is the most basic and important structural element in music.

It controls the innermost structure of each phrase and relationships between individual phrases. Rhythm could be considered the skeleton of all melodies, controlling their basic shape, while the pitch of individual notes could be considered the muscle and the flesh. Without the skeleton, everything else would collapse!

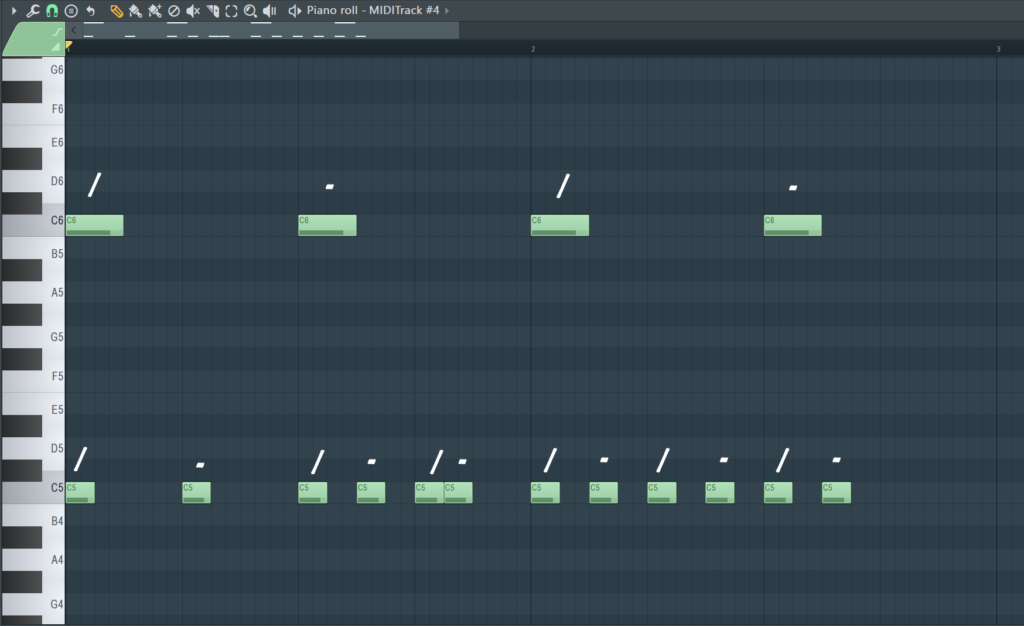

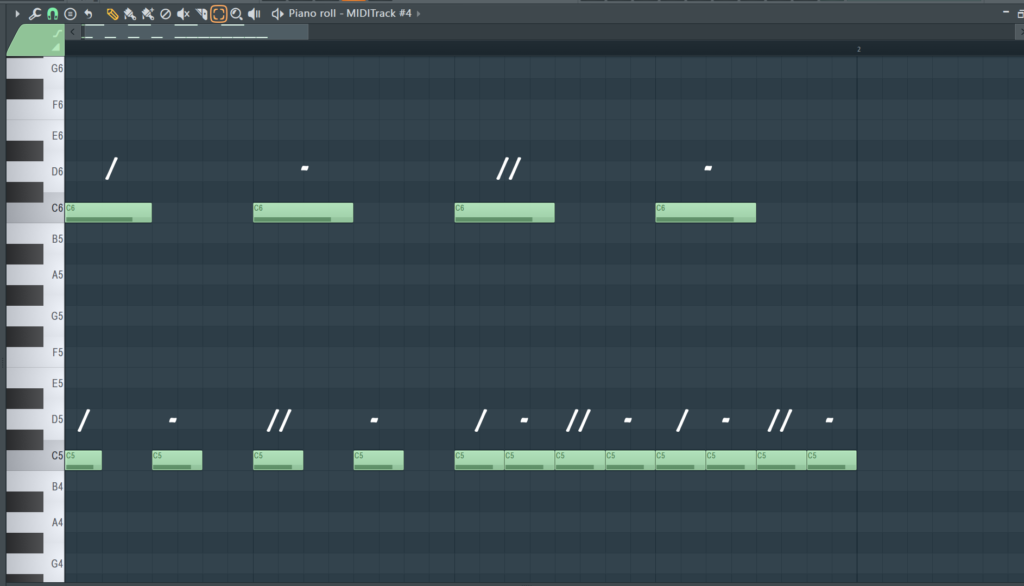

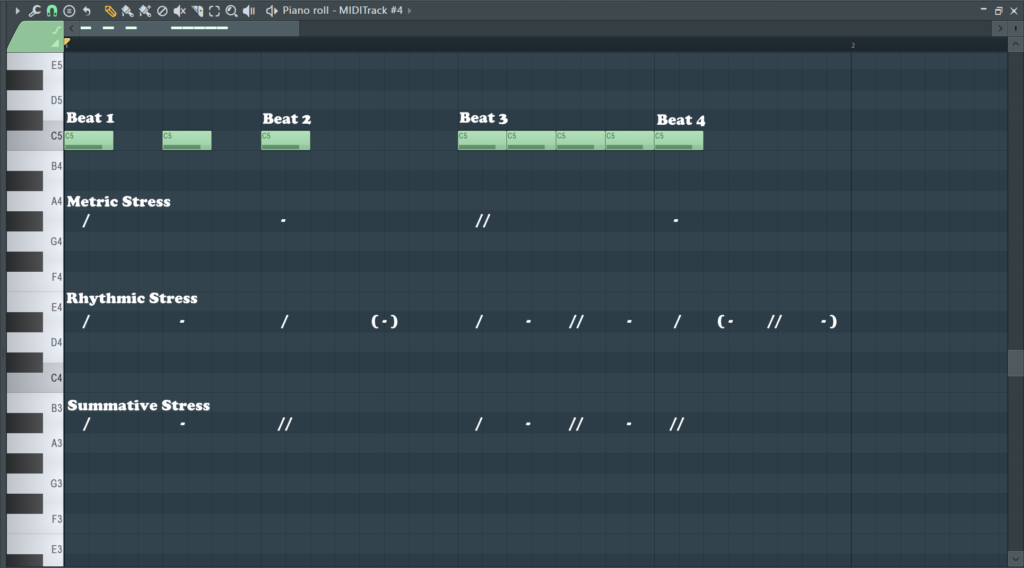

You must be wondering how rhythm is indicated. The notation of rhythm can be transcribed using the same symbols that are used in poetry: “/” represents a stress, “//” represents a secondary stress, and “-” represents no stress.

Let me illustrate this for you. Any group of 2 evenly divided rhythms forms a pattern of Strong /, Weak -, as shown below.

Any group of 4 evenly divided rhythms forms a pattern of Strong /, Weak -, Moderately Strong //, Weak -, as shown below.

Summative Stress

The stress pattern of a given rhythm reflects the simultaneous metric stress and rhythmic stress.

It also reflects the divisional (or sub-divisional) stress pattern that occurred in the rhythm of the previous beat. Metric stress always has a summative effect on the level of division or subdivision taking place. In compound meters or in duple meters that contain triplet rhythms, the stress patterns work summatively with one another.

In the image below, the difference between metric, rhythmic, and summative stress is illustrated for a rhythm.

Other Considerations in Stress

You must be wondering if there are exceptions to these rhythmic rules. As always in music theory, there are indeed exceptions.

Syncopation, or the accenting of a normally weak part of the beat, causes the syncopated note to be more heavily stressed.

Anticipations receive the stress of the beat anticipated and an additional stress due to syncopation.

Finally, a note following a rest (silence) receives more emphasis (unless it is less than the value of the note that it follows, in which case it simply acts as a pick-up for the following beat).

Overall, the most important factor in determining how much stress a note receives is the relationship of its rhythm to the meter and the rhythmic divisions that occur within the meter.

When a musical phrase ends on a stressed unstable tone, it conveys tension. When a phrase ends on a stressed stable tone, it indicates resolution, or the end of a melodic idea. For this reason, in looped-based music (such as EDM), melodies often end on unstable tones that generate a feeling of forward motion to the next piece of the song.

Stay Tuned for Part #2!

Did you find this tutorial informative or helpful?

Stay tuned for more by subscribing to this series below!

cool content.

What’s up, just wanted to say, I enjoyed ths article.It was inspiring. Keep on posting!

I could not resist commenting. Very well written!

nice artilce , thank you . keep it up

Looking forward to part 2