Do you want to learn how to use musical intervals and scales?

If so, you are in the right place.

Once upon a time, Hucbald was pissed.

Hucbald tried to make great music. He labored at it for years. And one day, he finally found the secret to success and released a viral song!

But his uncle became consumed by a violent jealousy…

“How dare he have more success than me!,” shouted Hucbald’s uncle, the diabolical headmaster of a monastery school. “I shall utterly destroy that devil of a nephew, and then I will extinguish him from the face of the Earth.”

Hucbald quickly fled from his home in terror.

Shortly after this, he sought protection from the bishop of Nevers. It is here, as a monk, that he plotted his musical comeback. Hucbald knew what to do. First, he analyzed ancient Greek music.

And then this Catholic monk did something sexy.

In 880, Hucbald wrote an awesome paper that revolutionized music theory. In it, he brilliantly “created” the church modes, and thus codified the musical scales in medieval Western music.

From this, the most proven tool you need to create stunning melodies developed: the major and minor scales.

Hucbald returned to his home, took over his uncle’s monastery school, and became wildly successful. And perhaps unsurprisingly, you too can enjoy this incredible success! It really is easier than you think.

So what’s the secret?

It’s simple. All you have to do is learn the modern version of Hucbald’s trick: how to use the major and minor scales. And if you want to learn this trick and improve your music, then you are in the right place.

Because this article shows you how to master scales in a snap!

So if you are ready for this, then let’s dive in.

All About Intervals: What You Need to Know to Make Awesome Music

Before we talk about scales, you first need to grasp the concept of musical intervals. This part is easy.

Think of intervals as the building blocks of scales.

When you play two different notes, one is obviously higher in pitch and another is lower. An interval is the difference in pitch between two different sounds. In essence, intervals describe the space that exists between two musical notes.

Imagine this: you play two notes on a keyboard.

When these two notes (in other words, an interval) are played at the same time, your ear will not only hear the two distinct pitches, but it will also process the harmonic relationship between them.

Let’s take a closer look at these intervals.

For now, we’ll just look at what are called simple intervals, which span 8 scale steps or fewer. There are 13 simple intervals. In the below picture you can see the names of these intervals and what they are.

As you can see in the picture, intervals are determined by the number of “spaces” between notes.

In Western music, these “spaces” are called semitones. A semitone is the interval between two adjacent notes in the traditional 12-tone Western music system. The minor second (pictured above) is equivalent to one semitone, whereas the major sixth is 9 semitones wide.

Okay, I know what you are thinking: why is an interval that is nine semitones wide called the major sixth?

The answer? The names of intervals are partially based upon the white keys on a piano (which is the major scale, but more about that later). In the above picture, you can see that the white notes on the keyboard are numbered 1-7. If you look more closely, you will see that the names of the intervals correspond to these numbers. The major sixth contains the notes labeled 1 and 6 on the piano, and the minor sixth contains the note below the one labeled 6 (but above note 5). Thus the names.

You may wonder why intervals are important.

Intervals form the most elementary unit of harmony in music. Some types of music are composed of intervals alone. And perhaps most fascinating of all, intervals tend to convey specific emotions.

The picture below shows associations between intervals and emotions.

And boom! At this point, it must be dawning on you that this has huge importance. The ability to use these intervals to convey emotions in your music will give you a great advantage!

But can this interval-emotion connection really be true?

Yes, but not necessarily. The emotions associated with intervals are essentially stereotypes. They are often based upon our own cultural views and history. Further, you may associate one emotion with an interval, while others may disagree.

See where we’re going with this?

Consider: The augmented fourth (a.k.a. the tritone) became known as the “Devil in Music” during the Middle Ages. Because key members of the clergy felt that it sounded evil, the church banned and/or discouraged the use of the interval. Partly due to this history, people later started using the augmented fourth to create sinister sounding music. As the augmented fourth was used more and more in a sinister context, it became a stereotype in our culture that the interval was evil. In reality, the interval is frequently used in chill or even upbeat music. An analysis of film scores showed that the augmented fourth is more frequently played in the background of emotionally positive scenes than negative ones.

In truth, the emotion conveyed by an interval is most dependent upon the context in which it is used.

Another major factor is whether the interval is dissonant or not. Dissonance refers to a harmonic clash between two or more notes, a harmony that sounds tense and unpleasant. In contrast, harmonies that sound pleasing and concordant are called consonant.

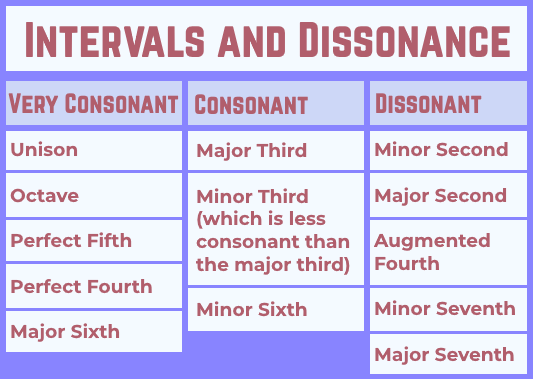

Look at the below chart. Intervals associated with negative emotions tend to be dissonant.

Dissonance does not fully explain the interval-emotion relationship. A notable example is the major third, which is considered to be a very harmonious, happy, (and in my opinion, cheesy) interval. The major third is associated with happy emotions more often than the perfect fifth. But oddly enough, the major third is more dissonant than the fifth!

It turns out that dissonance is more closely related to tension than emotion.

To summarize, the emotional connotations of intervals are useful, but not always reliable. In film music, only 4 intervals are overwhelmingly associated with positivity: The major third and major sixth are used to convey positive emotions more than any other interval. The minor third and minor sixth are used the most to convey negative emotions.

You can transpose intervals.

Allow me to explain. Transposition refers to the process of moving a collection of notes up or down in pitch by a constant interval. When you transpose an interval, the interval remains the same, no matter what notes it includes.

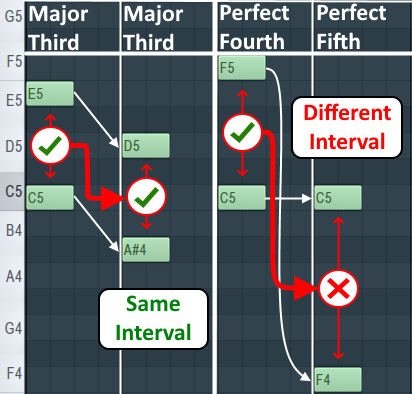

Stop and look at the picture below, where I have transposed an interval.

In the picture, I first transpose a major third. As you can see, I moved both the top and bottom note down by two semitones. The first and second intervals contain completely different notes, yet they are both major thirds. How can this be true?

Simple! An interval is defined by its width, not what notes it contains.

Look at the second example in the above picture. In it, I transpose a perfect fourth incorrectly. The first interval and the second both contain the notes C and F. But the width between those notes is different. The first interval is 5 semitones wide; The second is 7 semitones wide. This is because I did not move both notes by a constant distance (in semitones). Therefore, the first interval is a perfect fourth, but the second is a perfect fifth.

To sum it up, intervals are named for their width (in pitch/semitones), not what notes they contain.

Now we are ready to move on to scales! So let’s get busy.

Make Your Music Better By Unlocking the Power of Scales

Here’s the deal: Scales are likely the most essential tool for writing modern music. The word scale comes from the Latin “scala,” which means “ladder.” Naturally, you should think of scales as ladders. The steps of these ladders are musical pitches.

In other words, a scale is an ordered set of notes.

Modern popular songs often only uses notes that are contained within one specific scale. This limits the number of notes that can be used in the song, thus making it easier to write. It also imbues the song with a pleasant, cohesive quality.

The two most popular scales are the major scale and the natural minor scale (a.k.a. the Aeolian mode).

The natural minor scale is often simply called the minor scale. But there’s a problem! Why do I say this? There are actually 3 variations of the minor scale: the natural minor, the harmonic minor, and the melodic minor. The natural minor is the most common. For that reason, we are only going to talk about the natural minor here.

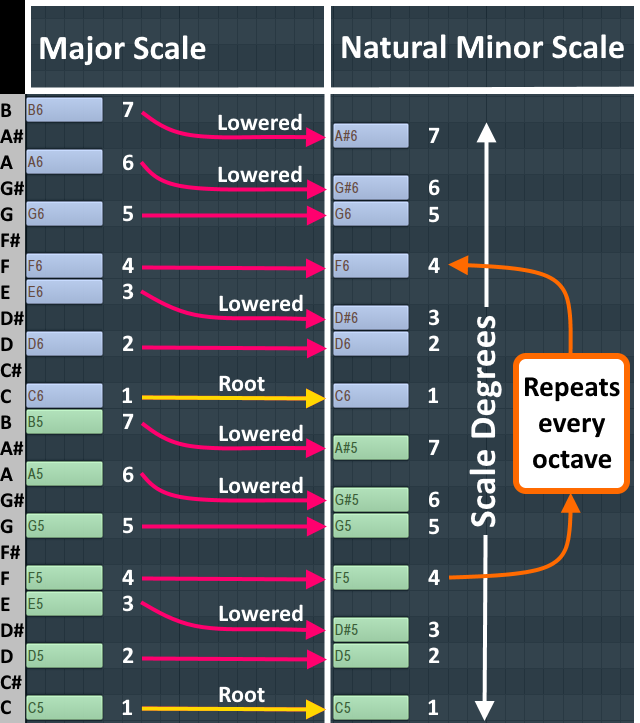

Look at the below picture. The major and minor scales are depicted.

As you can see, the major and minor scales are a collection of 7 notes that repeat every octave. The notes are numbered 1-7. (In case you don’t know, all of the names for notes on a traditional keyboard repeat every octave [12 notes]. Frequently, these names, such as C, or D#, have numbers appended to them to indicate their pitch. For example, C6 is one octave higher than C5, and C5 is 4 octaves higher than C1.)

The first note of the major or minor scale is called the root note (or alternatively, the tonic).

The notes of the scales are numbered in ascending order, starting with the root note. These numbers are called scale degrees. A scale degree describes the position of a note in a scale relative to the root. Each scale degree repeats every octave.

A scale is defined by the intervals between its notes, starting from the root.

In other words, a scale is defined by a sequence of intervals beginning from its root. For example, the minor scale is defined as follows: major second, minor second, major second, major second, minor second, major second. These are the intervals between the notes of the minor scale, in ascending order.

Both the major and minor scale can begin on any given root note.

The name of a scale is often written as [root note][name of scale]. For example, when the minor scale begins on the note C, it is called C Minor. In contrast, A Minor refers to a minor scale whose root note is A.

The below picture portrays the notes in the scales C Minor and A Minor.

In the picture, the C Minor scale is transposed to A Minor. How do you do this? First, you move the root note of the scale from C to A. Then, you add notes using the ordered list of intervals in the minor scale (major second, minor second, major second, major second, minor second, major second).

If you are a beginner, only use the notes contained within one specific scale to write a song.

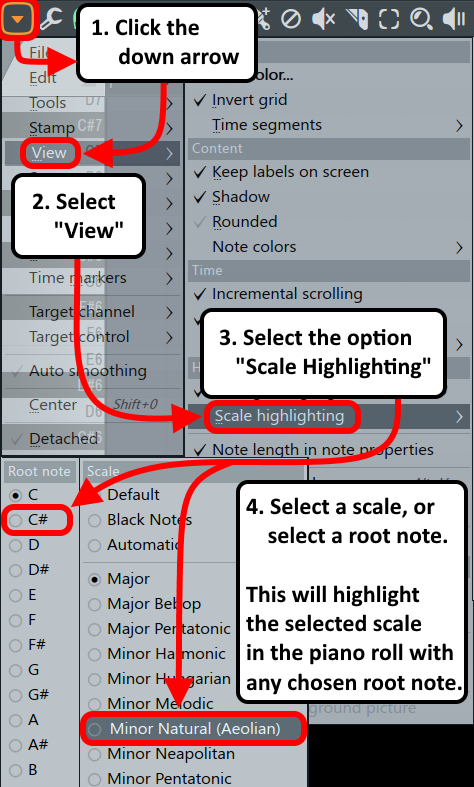

Only using the notes from one scale will make it much easier for you to write great music. And guess what? There is an easy way to remember the notes in any given scale! All you have to do is “highlight” the scale in the piano roll of FL Studio.

How do you do this? Look at the picture below.

Following the above steps will highlight a scale in the piano roll. The notes in the scale will become a light grey color. Notes outside the scale will be a darker grey. This makes it easy for you to pick the right notes!

When a song is written using a specific scale, we say it is in a key.

A key refers to the specific scale used in a musical composition. The name of any given key usually identifies the root note. When a song is written using the notes of the A minor scale, we say that it is in the key of A minor. Chords written using the F minor scale are in the key of F minor.

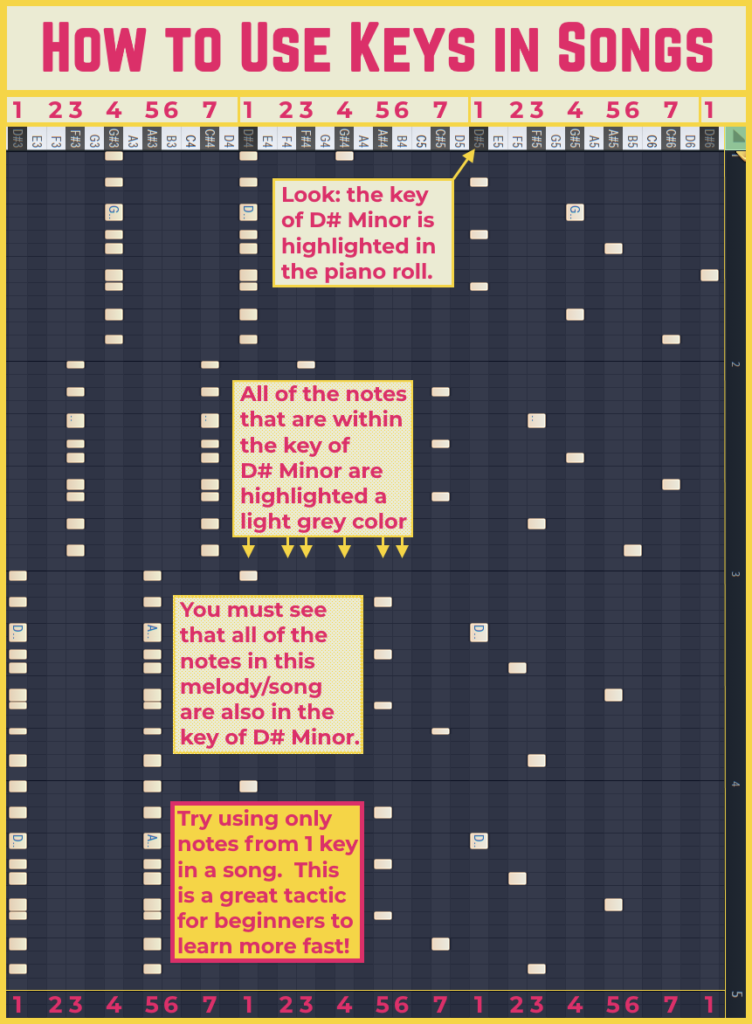

Check out the melody in the below picture.

All of the notes in both the melody and bassline are notes in the D# Minor scale. Further, the music revolves around its most common note: D#. For this reason, this composition is written in the key of D# minor.

But there’s a problem.

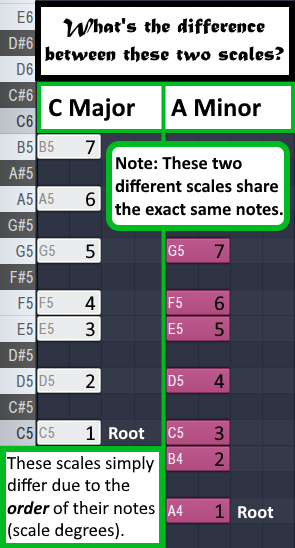

Why do I say this? Because some scales contain the exact same notes.

Take a look at this picture. It shows the C Major and A Minor scales. You can see that these two different scales contain identical notes.

So what’s the difference between these two scales?

Here’s a clue: scale degrees matter. Yep, you’ve got it! The order of the notes in these two scales are not the same. The root of the A minor scale is A, and its fourth scale degree is the note D. In contrast, the fourth note in the C Minor scale is F.

See where we are going with this?

The key of a song is not just dependent on its notes. The use of those notes matters as well. Many factors determine the key of a song. For example, most songs begin on their root note. The root also tends to be used more than most other notes in the song. The most defining factor is that the root note of a song usually sounds peaceful and “resolved.” Other factors exist, but we’ll cover them in another post.

One last thing before you go!

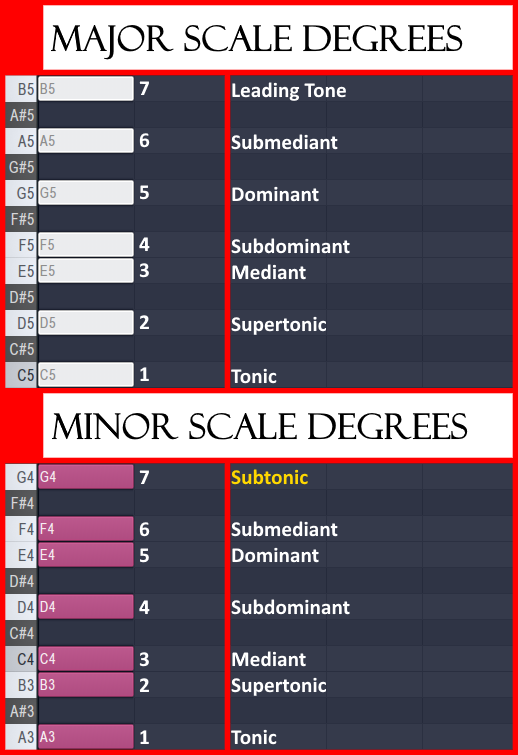

Scale degrees aren’t just numbers. They also have names. In the chart below, the names of scale degrees in the major and minor scales are listed.

These names are based upon the harmonies and chords that exist in these scales.

Luckily for you, we’re going to talk about chords in our next post!

So go ahead and subscribe to our blog to stay updated!